History of the Boone County Sheriff's Office

By Detective Tom O'Sullivan

Table of Contents

The Early Years

Although it happened almost 140 years ago, the incident on a dirt road in rural Boone County on a cool, crisp November day ominously reflects the reality of the contemporary deputy sheriff.

Sheriff James C. Gillaspy

Today, the serene, placid beauty of Rocheport stands in stark contrast to the days when it was a bustling commercial, political and industrial community on the banks of the Missouri River. The matter of law and order often was decided by social status or proficiency with a pistol.

It was a typical fall day in 1866 with Rocheport's shopkeepers displaying wares in their windows, the noisy clank of the blacksmith's iron and the horse drawn carriages hauling livestock and produce to the docked riverboats for destinations around the world. For reasons that are not particularly clear, anything from whiskey to simple treachery, a quartet of ruffians had spent a good part of the day riding horse-back through Rocheport shooting dogs, pigs, cats and anything else on four legs.

The three Adams brothers, John, James and Addison along with Frances Hornsinger were able to evade capture by Rocheport constables and fled Rocheport by way of the road to Columbia. As the four headed toward John Adams' home east of Rocheport they were met by Deputy Sheriff James Gillaspy, who had been in the area on other business and was completely unaware of the mayhem the group caused.

As Deputy Gillaspy rode past the outlaws, James Adams shouted "halt." When Gillaspy ignored his command, Adams drew his pistol and rode up alongside Gillaspy demanding in a furious tone that the lawman stop. Gillaspy paused and told Adams he had no time for such nonsense. An enraged Adams then fired one shot which barely missed Gillaspy. Gillaspy was able to return fire and wound James Adams in the shoulder. Both men were thrown from their horses and the fall caused Gillaspy to accidentally discharge his second and final round.

Gillaspy scurried on foot to the safety of Marion Cochran's farmhouse and borrowed another pistol, a navy revolver. Gillaspy returned to the scene of the shooting to find the four still present. Addison Adams is reported to have told his brother James, "There comes the damn son of a b----! Go and kill him!"

With just a few feet separating them, Adams and Gillaspy exchanged shots shattering the country calm. When the smoke cleared, James Adams lie mortally wounded next to his horse which had also been killed in the exchange.

Gillaspy, who would later become Sheriff of Boone County, was cleared of any charges by a grand jury in the shooting of James Adams, who died the following day. Addison Adams and Hornsinger were jailed on charges of intending to kill Gillaspy.

An incident some 67 years later had a much more tragic ending. Although horse and carriage had given way to the automobile and the candlestick and gas light deferred to a marvelous invention called electricity, a similar series of events unfolded with lawmen unaware the subjects they had encountered were extremely violent.

Back to TopThe Deaths of Sheriff Roger I. Wilson and MSHP Sgt. Ben Booth

June 14, 1933 was an unusually mild summer day in Columbia. Missouri Highway Patrol Sgt. Ben Booth called Sheriff Roger Wilson for assistance locating two suspects wanted for a bank robbery in Mexico, Mo. Sheriff's deputies today are reminded every time they travel to the department on Roger I. Wilson Drive of the events which unfolded that day near the intersection of present day Business Loop 70 and Rangeline Street.

Sheriff Roger I. Wilson

Sheriff Wilson and Sgt. Booth set up a checkpoint near that intersection hoping to catch the robbers who were reported traveling south from Mexico. Both officers had been present only a few minutes when a black Model A Ford coupe with two men inside rolled into the intersection.

Sgt. Booth stepped into the roadway holding his hand out signaling the vehicle to stop. Booth walked to the passenger side of the vehicle, which was apparently the norm in those days, and asked the driver of the vehicle, 21-year-old Francis McNeily, the basic questions—name, address, destination. The inside of the vehicle contained a cache of weapons. Although McNeily and his brother-in-law, convicted felon George McKeever were not the suspects in the Mexico bank robbery they were extremely dangerous men.

Although it is pure speculation, Sgt. Booth must have seen one of the many weapons in the car. He quickly reached through the passenger's window and opened the door which had been locked from the outside. As Booth pulled open the door McKeever shot Booth in the left leg with a Colt .45 semi-automatic pistol.

Sheriff Wilson, standing in front of the car, heard the shot and drew his weapon. But it was too late. McNeily fired two shots from a .38-caliber revolver striking Sheriff Wilson twice in the head killing him instantly. Although wounded, Sgt. Booth was able to pull his assailant from the car and a fierce struggle ensued over the Colt. The battle ended when McNeily exited the vehicle and shot Sgt. Booth in the back. As the fallen trooper lay motionless on the ground, McKeever stood up, retrieved the .45 and tried to shoot Booth again but the weapon jammed.

"You didn't kill him," McKeever was reported to have screamed as he took McNeily's .38-caliber revolver and fired another round into Sgt. Booth's heart. McKeever, according to witnesses, dusted his clothes off, brushed back his hair and the two returned to the vehicle and sped east. The owner of a nearby service station missed with two rifle shots as the getaway car passed.

Sergeant Ben Booth

Sheriff Wilson, two days past his 43rd birthday, died at the scene. Sgt. Booth, 37, a husband and father of two small children, died on the way to Boone County Hospital. The events which took place that sunny Wednesday afternoon and spanned the next three years were such the county had never seen before.

Roadblocks dotted the countryside and National Guard airplanes buzzed the clear blue skies like hawks in search of two cold-blooded killers. Orders were given to shoot at any vehicle not stopping at a roadblock.

Large posses of farmers, merchants, professional people and students fanned out through the county. A reward of $2,300 was offered for the killers capture. So incensed was the posse over the killings one newspaper reported the next morning that had the killers been caught "their being brought to the police station alive was highly unlikely."

All city and county offices were closed on Friday, June 16 in honor of Sheriff Wilson and Sgt. Booth. As both men lay in state at the Boone County Courthouse the manhunt continued, fueled by false rumors infamous gangster "Pretty Boy" Floyd and his accomplice, Adam "Dago" Richetti were the killers. The basis for the rumor was recent sightings of the two in Iowa and Floyd was known to shoot victims as they lay helpless. Bolstering this theory was witness accounts of one of the suspects primping and preening a bit after the final shot, another apparent Floyd trademark. Further adding to the Floyd/Richetti theory was the Kansas City Massacre at Union Station to which Richetti was linked and happened the day after the killings of Sheriff Wilson and Sgt. Booth.

The break in the case came in October, 1934 when police and Missouri Highway Patrol Capt. Lewis Means arrested McNeily at a farm in Allerton, Iowa. McNeily had been in a shootout the day before with sheriff's deputies and his description matched that of one of killers of Sheriff Wilson and Sgt. Booth.

McNeily confessed to the killing and implicated McKeever, who at this time was serving a bank robbery sentence in the North Dakota State Penitentiary. McKeever was brought back to Columbia and charged with the murder of Sgt. Booth. In exchange for turning state's evidence against McKeever, McNeily was given a life sentence for the murder of Sheriff Wilson.

At the trial, which was moved to Fulton in Callaway County on a change of venue, McKeever was found guilty and sentenced to death. In what was the last legal hanging in the state of Missouri on December 18, 1936, McKeever was executed after asking "forgiveness for all those I have injured." McNeily was paroled in 1947 and led, by all accounts, a trouble free life until his death in 1991.

Back to TopSheriffs of Boone County

| Sheriff's Name | Years Served |

|---|---|

| Dwayne Carey | 2005 - Present |

| Theodore P. Boehm | 1985 - 2004 |

| Charles E. Foster | 1977 - 1984 |

| Jack R. Meyer | 1974 - 1976 |

| Frank L. "Bud" Elkin | 1965 - 1972 |

| Glen Powell | 1949 - 1964 |

| Duke Moynihan | 1941 - 1948 |

| Robert L. Cook (see note 1) | 1941 |

| Pleas Wright | 1933 - 1940 |

| Roger I. Wilson (see note 2) | 1933 |

| Clyde Ballew | 1929 - 1932 |

| Roy Creed | 1925 - 1928 |

| Fred C. Brown | 1921 - 1924 |

| T. Fred Whitesides | 1917 - 1920 |

| G. Bert Sapp | 1913 - 1916 |

| Wilson Hall | 1909 - 1912 |

| Fountain Rothwell | 1905 - 1908 |

| Frank C. Bradford | 1901 - 1904 |

| William R. Baldwin | 1899 - 1900 |

| James T. Stockton | 1895 - 1898 |

| W.I. Roberts | 1891 - 1894 |

| John G. Evans | 1887 - 1890 |

| William A. Gooding | 1883 - 1886 |

| Josiah Wilson Stone | 1878 - 1882 |

| James C. Orr | 1876 - 1878 |

| James C. Gillaspy | 1872 - 1876 |

| James Carson Orr | 1870 - 1872 |

| Frank D. Evans | 1868 - 1870 |

| James Carson Orr | 1866 - 1868 |

| Joh F. Baker | 1864 - 1866 |

| James H. Waugh | 1862 - 1864 |

| John Martin Samuel | 1858 - 1862 |

| Jeremiah Orear | 1854 - 1858 |

| Joseph Beeler Douglass | 1850 - 1854 |

| William T. Hickman | 1848 - 1850 |

| Thomas C. Maupin | 1844 - 1848 |

| Frederick A. Hamilton | 1840 - 1844 |

| John S. Martin | 1836 - 1840 |

| William S. Burch | 1832 - 1836 |

| Thomas C. Maupin | 1830 - 1832 |

| Harrison Jamison | 1826 - 1830 |

| James Barnes | 1822 - 1826 |

| Overton Harris | 1821 - 1822 |

Note 1: Sheriff Robert L. Cook served from January 1, 1941 through May 7, 1941 and died in office.

Note 2: Sheriff Roger I. Wilson was killed in the line of duty on June 14, 1933.

History of the Boone County Jail

Original Jail: 1934-1991

View from Ash Street to the north side of the 1934/1978 jail, located on the north part of the Courthouse Square.

This view is looking to the Southeast. You see on the left side of the picture the original 1934 Sheriff’s Quarters and offices, and the middle would be the actual 1934 Jail building that held a maximum of 24 detainees. The remaining building is what is referred to as the "78 addition", as it was the result of a bond issue approved by the City of Columbia, to construct a 48-bed addition on to the jail, for housing of municipal prisoners as well as county prisoners. This "arrangement" allowed the City of Columbia to close their existing Municipal Jail located on the upper floor of the present Columbia Police Building at 601 Walnut. You can note the "officer entrance" to the right of the sign and the "public entrance" to the left of the sign. The basement of jail maintained the control room, property storage, visitation, holding, kitchen, and emergency generator. A garage door located right of the existing photograph was intended for a vehicular sally-port, however it was never constructed large enough to practically use and was merely a port of deliveries to the jail for the duration of the building’s use.

View towards the interior officer entrance from the control room of the jail.

This is the view towards the interior officer entrance from the control room of the jail. You notice the row of camera monitors on the right and the board of control buttons on the counter. Basic jail staff included one control room officer, a supervisor, and one to two roving officers assigned to the floor. All movement by detainees had to be monitored and assisted by officer supervision. There were no computers, no lap-top units, and all reports were hand written; the only typed report was the 0700 report which chronicled the day’s arrest for the preceding 24 hours period. In the 1970s, staffing was significantly less, with only one officer in the jail. Jail checks had to be accomplished by the road officers who came into the jail specifically for that purpose. In the early 1980s greater responsibility and staffing was exhibited by Sheriff's and the jail become a more self-sufficient model of administration and operation.

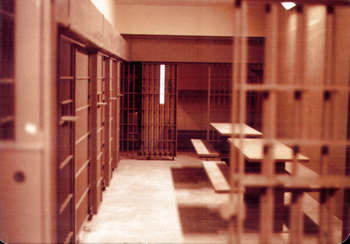

View into one of the 12-man housing units located in the 1978 addition to the old jail.

This is a view into one of the 12-man housing units located in the 1978 addition to the old jail. Six two-man cells placed in an "L-format" around two metal tables. No real room to exercise, or have much personal space. An exercise yard was established with the 1978 renovation, however, the fencing was never secure enough to allow actual exercise and staff was never in place to supervise that process as well. Female detainees were generally housed in the 1934 section of the jail, however, from time to time, one of the 12-man tanks were taken over by an exploding female detainee population. Due to the open view into the cells, blankets were hung on the cell fronts to afford the female detainees some privacy when that occurred. You will notice there are no phones in this cell block. Phones were dialed by officers, who handed the receivers to the detainee through the bars. This was very staff intensive and small privileges like phone calls to family enjoyed by today’s detainees were rare in the old jail.

New Jail: 1991-Present Day

The current Boone County Jail was opened on February 28, 1991. The original jail/Sheriff's Operations Building complex, existed of four buildings with a Vehicular Sally Port. The entire project comprised approximately 54,000 square feet at an initial cost of about 6.8 million dollars. The jail occupies three and one half buildings and approximately 35,000 square feet of space. The remaining 19,000 square feet of program space is devoted to joint mechanical space and the Sheriff's Operations.

This new jail is an "indirect supervision" model which allows for viewing into the cell blocks by way of windows and camera monitoring by control room officers as well as roving officers that enter in the cell blocks and housing units on a frequent basis. Each of the three detainee housing structures includes a central control room surrounded by 5 to 7 housing cell blocks. Each cell block holds from six to twenty four detainees of various gender and offense classification.

The original jail had 134 beds for custodial detainees and a 50-bed Work Release center split with 35 beds for men and 15 beds for women detainees. In 1999, we divested our Work Release program and contracted with Reality House Incorporated to manage that function. We conducted a major renovation of our work release facility and created a five unit classification custody area primarily for female detainees. With the addition of add-on bunk space and absorption of program space we added 26 additional beds in our original custody buildings and increased our total detainee capacity from 134 to 210 detainees. All this was done within the existing hardened environment of the original 1991 construction. As a result of the total use of existing hardened space we were forced to add a small storage building accessible to our admin building. Although our total maximum capacity is 246, due to classification and gender needs, we operate in the 210-220 capacity as a daily operational capacity.

Detainees that exceed our operating capacity are housed frequently at Reality House Inc., Cooper County, Chariton County, Howard County, Callaway County, Randolph County, and Montgomery County.

Back to Top